Link https://youtu.be/xBcTOje1v4s

The Peterloo Massacre

Transcript

Note: Melvyn Bragg interrupts a lot in this segment and often appears to do so without a fully formed question in mind. So, I've dealt with this in two ways, either typing out what I believe he meant to say based on the context of the discussion and the replies, or failing that cut out the interruptions.

In addition while this talk on Peterloo is important particularly as it relates the other events of political and economic change that surround the meeting on St. Petersfield it does still contain some myths which I've decided to respond to via footnotes.

Note: Melvyn Bragg interrupts a lot in this segment and often appears to do so without a fully formed question in mind. So, I've dealt with this in two ways, either typing out what I believe he meant to say based on the context of the discussion and the replies, or failing that cut out the interruptions.

In addition while this talk on Peterloo is important particularly as it relates the other events of political and economic change that surround the meeting on St. Petersfield it does still contain some myths which I've decided to respond to via footnotes.

Melvyn Bragg:

Hello in 1819 Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote

“I met Murder on the way—

He had a mask like Castlereagh—

Very smooth he looked, yet grim;

Seven blood-hounds followed him:

All were fat; and well they might

Be in admirable plight,

For one by one, and two by two,

He tossed them human hearts to chew

Which from his wide cloak he drew.”

As Foreign Secretary Robert Stewart Castlereagh had successfully

coordinated European opposition to Napoleon, but at home he repressed the

reform movement and popular opinion held him responsible for the Peterloo massacre

of peaceful demonstrators in 1819.

Shelley’s the Masque of Anarchy reflected the widespread public

outrage and condemnation of the government’s role in the massacre.

Why did a peaceful and orderly meeting of men, women and

children in St. Peters Field Manchester turn into a bloodbath? How were the

stirrings of radicalism in the wake of the Napoleonic wars dealt with by the

British establishment and what role did the Peterloo massacre play in bringing

about the Great Reform Act of 1832?

With me to discuss the Peterloo massacre are Jeremy Black Professor

of History at the University of Exeter, Sarah Richardson Senior Lecturer in

history at the University of Warwick and Clive Emsley Professor of History at

the Open University.

Jeremy Black, the early 19th century, it was a

time of great anxiety for the British government and the spectre of descent and

so on. We can trace it back, I know you historians want to back to Adam, but let’s

start with the French Revolution in 1789 and kick that off into what we’re

going to talk about.

Jeremy Black:

French Revolution breaks out in 1789, it frightens many

members of the British establishment because there is a comparable movement of

British radicalism which looks to France for inspiration. Though in part that

movement is actually indigenous and looks back to earlier British traditions.

Britain goes to war with Revolutionary France in 1793, and the war goes badly. And

in the context of an unsuccessful war in the context of anxiety about

radicalism at home and indeed in Ireland as well, there’s the growing use of

what according to some commentators is repression against signs of radicalism. And

that in a way provides the context, the long context for Peterloo.

Melvyn Bragg:

So we have the suspension of Habeas Corpus, we have the

Treasonable Practises Act, we have Seditious Meetings Act. I mean really

ferocious suppression of any sort of free speech, any real assembly, any

written work. At the same time to be fair one has to say that the government

was terrified that they were going to be invaded by the powerful French, that

they were going to be overturned, the Monarchy wrecked, the whole system would

be wrecked, so there was a real threat. We can look back now and say oh the Liberals-

a really serious threat going on.

Jeremy Black:

Oh yes there was a really serious threat, there’s also an

important point on which historians are very divided. Um, historians are very

divided as to the extent to which the governments sentiments rested also on a

wide springing of a popular conservatism.

I mean it’s not that everybody in the country is radicals

and they’re being held down by a brutal and oppressive government. Such an you

know that that’s not the case. There is an important populist radical stream

and there’s an important populist conservative stream. And both of them

actually interact right through the end of the 18th and the early 19th

century.

Melvyn Bragg:

That’s actually what makes it so interesting, Sarah

Richardson can you tell us about the ideological impact of the French

Revolution, develop what Jeremy said into works which were around at the time,

I’m thinking principally of say Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man.

Sarah Richardson:

The Rights of Man

is extremely influential, it encapsulates this concentration on universal rights,

so ties in with this idea of reform. I think that whilst Jeremy’s right that

some of the traditions of radicalism go back, the emphasis is coming out of the

Enlightenment and ideas to do with what’s happening in France are about universal

rights, rights for everybody. Rights that don’t rely on Aristocracy, don’t rely

on birth, don’t rely on income but the rights that you were born with, and this

is something that clearly the working-class radical movements pick up on.

Melvyn Bragg:

Can you tell us how Thomas Paine – lets stick with Paine,

but you can please bring along another writer- he’s very useful and also

important in America and in France as well as in this country. The idea of

rights was in itself we just – listeners might just thing well there you are-

but it was a radical idea wasn’t it, you didn’t have power because of privilege,

you didn’t have power because of divine right, had rights because you were a human

being born, where by being born were given you.

Sarah Richardson:

That’s right and I think that when you look at it in terms

of political rights and civil rights this is a very radical idea. The British

constitution is really based on property, on the idea that interests are

represented that people aren’t represented, numbers aren’t represented but interests

are represented and you are represented virtually by the fact that in Parliament

for example you have members from across the country, they’re not necessarily

voted in by the whole population but they are representing that population via

their interests.

Now what Tom Paine is-

Melvyn Bragg:

It’s a Parliament of Property and Power rather than a

Parliament of people.

Sarah Richardson:

That’s right, and what Tom Paine is really saying that to

sweep that system away that individuals have rights, that you should be able to

participate as a citizen in the country and voting rights are one aspect of

that, that can be recognised.

Melvyn Bragg:

Can we talk a bit about the industrial unrest that preceded

the events at Peterloo? Peterloo 1819 war finishes 1815, big industrial unrest started

before that. You have the Luddites and then the Blanketeers marching, smashing

machines, resenting the fact that machines were taking away their jobs and

children and women and so on. And I mean anti Industrial Revolution turning

into political action especially up in the north.

Sarah Richardson:

That’s right, the Luddite rebellions are very much anti

industrial, and in some way quite conservative in resisting change that clearly

this feeds into the political unrest, the fact that these people have no

rights, they’re not represented, their interests aren’t being represented

virtually.

Melvyn Bragg:

But we’re talking about marches, smashing machines, violence,

meetings against the Acts that have been put in -as Jeremy said in the beginning-

during the French wars.

Sarah Richardson:

Lots of violence, and the Blanketeers march is important in

this context, because its one of the largest protests in the country, around 10,000

people and its just a couple of years before Peterloo in 1817. And again, the

magistrates send in soldiers to stop this march. That the Manchester textile

workers are trying to organise a march to London to present a petition to the

Prince of Wales, Prince Regent to ask him to intervene in the economic

distresses in the country.

Melvyn Bragg:

Okay, Clive Emsley we’ve already heard about the Napoleonic

wars and about the appetite for radical politics, how were they surviving when

habeas corpus was suspended, when the Treason Acts and so forth. How were they

how do they keep going?

Clive Emsley:

There are restrictions on mass meetings, it doesn’t stop people

talking. And it… part of the radical movement does appear to go underground,

there is an interesting debate among historians, I mean no one is quite agreed

on the extent to which English radicalism is almost entirely constitutional and

uhh the alternative view is that there is an extremely strong underground revolutionary

element within English radicalism.

Melvyn Bragg:

When we’re looking at the radicals over here we split again

now, we have this sort of Constitutional element which we’ll be coming to at

Peterloo, and then we have the real revolutionaries and it could be suggested

that there were before Peterloo there were a couple of attempts at which could

be called revolution in this country.

Clive Emsley:

Oh yes, and those attempts actually go back to the to the

1790’s. There looks to be a group of individuals who are working towards a

revolution within the country in the late 1790s. in 1801 you get the conspiracy

of Colonel Despard, who was a comrade in arms of Nelson but is executed with

several members of the Guards for attempting to kill the King, or at least that

was the story.

And then you have no serious revolutionary activity of that

sort but you get Luddism. And Luddism is infected with these radical ideas or

would seem in certain areas to be infected with the radical political ideas and

that’s an interesting new departure, that you have industrial action linked

with political ideology.

Jeremy Black:

One of the things about Luddism is that the government’s

response is to send troops. Thousands and thousands of troops are deployed in

Nottinghamshire and in the Yorkshire area, so in the absence of a major police

force, I mean this is the pre age of –

Melvyn Bragg:

Are we still talking of around Peterloo time?

Jeremy Black:

Oh, yes, yes of course you know they are deploying thousands

of troops against what appears to be this umm working-class movement which has a

political tinge which they don’t understand.

Melvyn Bragg:

Yeah, let’s let’s get to Peterloo. Sarah, its called by the

Manchester Patriotic Union society, and given what happened, given what became

thought of by some as terrible, they the Manchester Patriotic Union Society

called this meeting and at the end of their meetings they sand Rule Britannia

and God Save the Queen, which might surprise somebody thinking this was a bunch

of terrible radicals. Can you just tell us what they were after? This outfit

the Manchester Patriotic Union Society?

Sarah Richardson:

Well they’re raising profile, they’re trying to get reform

on the political agenda. As we’ve seen the government shows no interest in

advancing, - it’s a Tory government they’re interested in repressing this sort

of move they’re not interested in legislating or changing anything. So they’re

trying to use numbers, they’re trying to use peaceful protest, and they’re trying

to raise consciousness by inviting important speakers like Hunt, also John

Cartwright whose another leading radical to try and spread the message so it’s,

they’re really trying to get reform on the agenda.

Melvyn Bragg:

And they’re Constitutionalists, they believe in constitutional

monarchy, to get it into a particular local context you have this booming city,

a massive city of Manchester, with no representation in Parliament whatsoever,

and you have a couple of houses, literally a couple of houses in Wiltshire

which sends up an MP. So this is, this is what they’re on about. Clive Emsley

one of the members of the Manchester Patriotic Union Society spoken of was

Henry Hunt, can you tell us something about him?

Clive Emsley:

Well he’s not umm he doesn’t come from Manchester, he’s a

Wiltshire farmer a real John Bull character, famous for his pugilism. And he’s

a fantastic speaker, and can hold a crowd and convince a crowd and has

reputation as the finest radical orator in the country. That’s the reason why if

you want to get a mass meeting then you get orator Hunt with his big white top

hat to come and address them.

Melvyn Bragg:

It’s a wonderful picture, I love the fact that he’s a

hunting, shooting, farming, fishing John Bull man going to Manchester, he went

there to address them on what were then thought to be radical though

constitutional issues.

Clive Emsley:

Yeah, and Hunt is a Constitutionalist, there are there are

other radicals, this underground revolutionary element is continuing at the

same time. And Hunt knows them and certainly in London he is involved in a

meeting at the end of 1816 which leads to serious disorder. But Hunt actually

manages to control the bulk of the crowd while the extremists are all for

storming the tower.

Melvyn Bragg:

Sorry Jeremy you want to say something?

Jeremy Black:

Yeah, Hunts part of a tradition, Burdett before him, Cartwright

before him of radicals who want to work within the system to reform it, and

many of whom are strong in the north and its no accident that the major

reforming movement of the 1780s is the Yorkshire Association. The north of England

has a very powerful reforming-the constitutional reforming tradition.

Melvyn Bragg:

So they call this meeting Sarah Richardson, they cleared it

with the magistrates, they were going to be on St. Petersfield, we’re told that

up to 50,000 people turned up, there are masses of eye witnesses, it was

massively reported. They got their on the day in their best clothes as we

understand, which is a factor because this is a celebration, and they were told

no weapons and so on.

So they get there in the morning, can you just tell us

through to the speeches and then what happened?

Sarah Richardson:

Around midday the square is filling up with people, around

50,000 people by midday and another 10,000 people by an hour later. The magistrates

are watching, there are a number of middle class commentators are also

watching. But its fair to say the majority of the people almost all the people

in the square are working class. Who’ve come there in their best clothes to listen

to the speakers and peacefully.

There’s no real sign of disorder, so around twenty past one

the speakers arrive and there’s a platform at one end, they’re taken towards

the platform in order to begin their speeches about 1:30.

Melvyn Bragg:

This is Hunt with his white top hat and Carlile?

Sarah Richardson:

Yeah, I mean one of the other people is a member of the

Manchester Female Patriotic Union called Mary File, which is the female reform

movement that’s set up, there’s a number of these set up around the country. So,

women are important as participants in the crowd, but also speakers, she’s up

on the platform with Hunt and Carlile and other leading Manchester radicals. And

the press is there, the Times has sent its reporter, the local press are there

so they’re also in the square.

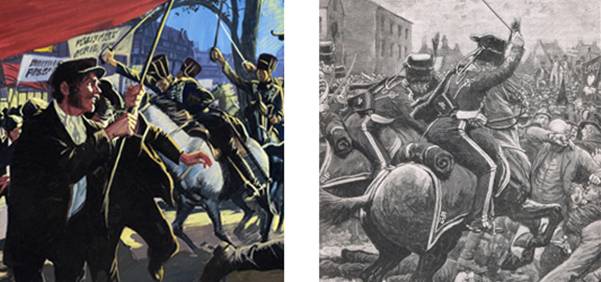

So, the speakers arrive, the magistrates then decide that

Manchester is in great danger and there’s going to be disorder so they decide

to send the police in to arrest the speakers. The police turn to the magistrates

and say we can’t go in unaccompanied we need soldiers, so you have the Manchester

and Salford Yeomanry who’ve been set up I think after the Blanketeer protests and

Manchesterers wanted their own local militia partly as Jeremy said because there’s

no police force so therefore, they want their own militia in order to control disorder.

Melvyn Bragg:

So, these are chaps on horses with sabres?

Sarah Richardson:

On horses with sabres. And then there is the regular army

Hussars as well around there backing them up. So, they send the soldiers in,

the crowd resist and try and stop them from getting to the platform, link arms.

And that’s when they get the sabres out, the horses out and basically slash

down the crowd and kill a number of people, official estimates say eleven but-

Melvyn Bragg:

Well this new book here that I have before me that just came

out by Michael Bush says that they’ve done the sums again and that its

seventeen and over six hundred wounded.

Sarah Richardson:

I think that that’s entirely believable.

Melvyn Bragg:

And Clive Emsley, you’ve got the Yeoman cavalry going, can

you tell us a little bit more about that and what was their relationship with

the Hussars, the regimental cavalry that backed them up, these men some of whom

had fought at Waterloo? Actually, some of the people who had been killed fought

at Waterloo as well. Its all very complicated, just tell us about the Yeomanry

and then what part the Hussars play.

Clive Emsley:

Well in fact sending the Yeomanry in was probably the biggest

mistake, because the Yeomanry were generally speaking Millowners or the sons of

Millowners or farmers the sons of farmers. These were, these were local

volunteers who trained once a month or whatever. And this is, this is almost a

kind of manifestation of class war. Because these are people who employ the

individuals in the crowd. And so sending those individuals into the crowd who

are not as well trained by any stretch of the imagination as the regular

cavalry, with this potential for class hostility was an astonishingly stupid

thing to do.

Melvyn Bragg:

One thing that I think we should record because I thought it

was very interesting, the Hussars the professionals, the regimentals, deeply disapproved

of what the Yeomanry did[1].

Clive Emsley:

Oh yes, and, and there are, one of the Hussars Lieutenants,

lieutenant Joliffe wrote an account in which he describes, and indeed The Times

reporter describes the Yeomanry cavalry cheerfully sabreing people and the

regular cavalry being ordered not to do that, specifically not to do that.

I mean there’s also the problem of when you, the physical

problem for the soldiers of sitting on a horse in a very dense crowd, and

certainly the regulars were told to use the flats of their blades, so they’re

having to control their horses with their left hand, and twist their wrist

given the structure of a sabre grip, twist their wrists to bring down the flat

of the blade.

Now even bringing down the flat of the blade means an edge

can slice an ear or whatever but an extremely difficult thing to do even for a

good swordsman on a horse[2].

Melvyn Bragg:

Excellent, now then Jeremy you’ve mentioned journalists were

there, and they were arrested and rather surprisingly the journalist from The

Times was arrested- that wasn’t surprising, what was surprising was that the

editor of The Times went through the roof and insisted on publishing everything

he could about how black a day it was, and this was very influential, can you

talk us through that?

Jeremy Black:

One of the things that are worth remembering is that there

isn’t a conservative establishment in which everyone has the same opinion. I mean

The Times is a conservative newspaper but it is equally horrified at what is

going on as a lot of reformers are. The newspapers reported it fully, they

brought home to a national and indeed international audience because people

abroad were able to understand what had happened by reading the London newspapers

that something had happened in the provinces.

And again, this is a relatively new development, in essence in

the 18th century the reporting in the London press, the national

press of what happened in the provinces was generally quite small, quite modest

and by having reporters actually physically there, you know these are early

days for having newspaper reporters, most newspapers had no reporters they

essentially just used cut and paste, taking reports from other newspapers

elsewhere. By actually sending reporters by actually then when their reporters

got arrested taking local Manchester press reports-

Melvyn Bragg:

The Times reporter got arrested.

Jeremy Black:

Got arrested, and so they then took Manchester press reports

and published them through the London press they made Peterloo- I mean Peterloo

anyway was very important- but they made it an incredibly totemic moment

through the newspapers.

Melvyn Bragg:

Did the reporting as it was done stir up a body of opinion

then which, which had an importance?

Clive Emsley:

Oh yes absolutely, I mean for one thing it provokes extremist radicals, it also it embarrasses a lot of the conservative establishment. And I think the government is in a bit of a quandary, I mean what, what can we really do about this? We’re scared about the potential for some form of insurrection, some extreme radicalism. But we can’t start criticising our magistrates, or prosecuting our magistrates.

Oh yes absolutely, I mean for one thing it provokes extremist radicals, it also it embarrasses a lot of the conservative establishment. And I think the government is in a bit of a quandary, I mean what, what can we really do about this? We’re scared about the potential for some form of insurrection, some extreme radicalism. But we can’t start criticising our magistrates, or prosecuting our magistrates.

So, the government is in a bit of a cleft stick here. But there’s

also a very serious impact on the well even on members of the Manchester

Yeomanry cavalry. Less than ten years after leading the cavalry, the Manchester

Yeomanry cavalry a cotton manufacturer HH Burleigh is actually calling for

Parliamentary reform at a mass meeting in Manchester. Which is an interesting volte

face.

Melvyn Bragg:

But in a sense the government if we’re looking at it terribly

crudely and I do apologise won. Henry Hunt in the white top hat the John Bull,

two and half years in prison, Richard Carlile newspaperman six years in prison.

His wife kept on publishing his newspaper, she’s put in prison while pregnant

for two and a half years, his sister she’s put in prison for two and a half

years. So, in that sense the clampdown continues.

Carlile manages to use his trial to get around the

suppression of the press because trials were published and therefore there’s a

further inflammation of public opinion from his trial. Tell us about that

Sarah.

Sarah Richardson:

Well Carlile’s interesting because he actually escapes, he’s

one of the few people that escapes from Peterloo, from the square. He manages

to get to London, he’s harboured by local radicals and then he gets to London

an account in his own newspaper. He gets six years as you say where Henry Hunt

gets two and a half, because he is prosecuted for publishing seditious libel. And

so therefore-

Melvyn Bragg:

The seditious libel being the account of the meeting?

Sarah Richardson:

Yeah, and for insurrectionary words and so on. But his trial

is an incredibly important piece of political theatre, I think. Because one of

the things he does in his trial for example is read out Tom Paine’s Age of Reason because trials can be

reported verbatim and while you cannot publish accounts of Peterloo without

being chucked in prison or arrested-

Melvyn Bragg:

Well The Times did, I mean they were to powerful to chuck in

prison.

Sarah Richardson:

Lots of journalists are arrested at this time, and there’s a

lot of censorship and the government introduces six Acts after Peterloo in

order to further repress the press.

Melvyn Bragg:

Yes, we must say that as well, six further Acts of

repression were introduced as a result of Peterloo.

Sarah Richardson:

Yeah, partly for seditious words but also to increase the tax

on newspapers, to try and tax them out of existence. So, you’re driving the

radical press underground.

Melvyn Bragg:

Quickly Jeremy, I started this program with a couple of

stanzas from a very long poem by Shelley, he’s over in Italy, and he gets word

of it he really wakes up and dashes it off. He writes it in 1819 but its censored

until 1832, but did it have any effect? Is he engaging yet another constituency

with this? Presumably it was passed around.

Jeremy Black:

Yes, very much so. I mean romantic opinion; fashionable

opinion is helped by responses such as Shelley’s to feel that the government system

in some way is corrupt. I mean in practical terms there are very serious issues

in British society, I mean how do you manage economic difficulties, how do you

manage political change, and sometimes the emotional response isn’t always

appropriate.

But there is no other response to Peterloo other than an

emotional response because it was such an appalling mishandling of a situation.

And I, I mean looking forward the, the climate of opinion helps to make it very

very difficult, to defend what increasingly to many people seems to be

indefensible. Which is the political system which is the representational

system.

Melvyn Bragg:

But that’s a slower burn Jeremy, what happens in the

aftermath of Peterloo if you look is that actually the government gets its way.

I mean people say oh sorry oh dear oh dear, but there are six Acts that come

in. Tax the newspapers out of existence, absolutely no meetings whatsoever,

tying everybody’s hands, and then it isn’t as if Peterloo’s the end of something,

could be said to be the beginning of something, because a year later we have

the Cato street conspiracy. Just tell us why that was important Clive.

Clive Emsley:

Hunt goes back to London and there is an enormous

celebratory welcome for him, and the extremists with whom he’d had these slight

links in 1816 and 1817 who went by the name of the Society of Spencean Philanthropists.

They followed a kind of proto Communist Newcastle schoolmaster called Tom Spence,

who felt everyone should get back to the land and we should stop all this

industrialisation and there should be equality.

Then there are three principal leaders Doctor Watson and his

son and a former militia officer called Arthur Thistlewood. And these people

have already attempted at least one coup d’état, and after Peterloo they are

incensed and say something must be done.

Melvyn Bragg:

So what do they do?

Clive Emsley:

They plot to kill the cabinet at a cabinet dinner.

Melvyn Bragg:

Why did it take so long then? Everybody thinks the Peterloo

massacre brought reform, but its 13 years before there’s reform which actually

carries on the theme that the governments still in charge. The Whigs are an absolutely

rotten opposition, Tories got Wellington their great Icon and despite how much

he might have been disliked so very quickly Jeremy, so sorry we’ll have to do

this bit again some other time. Why did it take so long to get to the Great

Reform Act which wasn’t all that great anyway when you think about it, but

still why did it take so long?

Jeremy Black:

Why’d it take so long? Because first of all there’s an

important conservative populist side which we haven’t talked about, second of

all because the radicals and reformers are divided and third of all because

what historians need to do is look at processes as well as structure. Structure

demands change as it were but the process of getting change is much much more

complicated. Incidentally it leads to a whole lot of big riots. Peterloo was

not a riot the riot was by the Yeomanry, the riot was actually by the Yeomanry,

but there are big riots in the 1830s in Bristol and in Nottingham by pro

reformers and that is very interesting because the relationship there between

popular activism and for political change is a complex one.

Melvyn Bragg:

Sarah?

Sarah Richardson:

I think that you can’t get change without a government that’s

going to introduce change, and the basic fact is the Whigs are not in power,

they’re the only party that is going to embrace any sort of change and so that

is the straight answer why you don’t get reform until the 1830s.

Melvyn Bragg:

Sorry, Jeremy mentioned the phrase conservative populism,

can you just amplify that into two paragraphs?

Clive Emsley:

Um, yes I mean, it links with the notion of the freeborn Englishman

and the idea of the English Constitution, still being generally speaking

superior and the English being superior to everybody in Europe.

Melvyn Bragg:

So that is, that conservative populism slowed it down a bit?

Jeremy Black:

I think conservative populism slows it down, I think Sarah

is absolutely right, Whigs aren’t in power[3], Tories aren’t going to introduce

it. No two ways about it and as you say 1832 is not I mean people think of it

in the 19th century as a great reform act, the practicality is that

most males still don’t have the vote, women of course don’t have the vote and

its only some parliamentary boroughs that get the vote. Though Manchester crucially

does.

Clive Emsley:

And the interesting thing of course is that an enormous

number of males lose the vote in 1832. Which is something that is conveniently

forgotten very often, in the notion of a progressive linear development in the

vote in British society.

Melvyn Bragg:

Well thanks very much for being such good sports, I’m sorry

about that stampede, there you go, Sarah Richardson, Clive Emsley and Jeremy

Black thank you very much indeed and next week we will be talking about Heaven.

_____________________________________________________

Footnotes:

1: There is a myth about Waterloo that lays the blame for the violence squarely on the shoulders of the Yeomanry, a volunteer militia while laying praise on the regular military for discipline and restraint. There is strong evidence that individual members of the Hussars and infantry behaved more humanly, Lieutenant Joliffe whose account was very important in exposing the establishments version of events as largely fictitious also contains references to the army attacking and dispersing the crowd.

Additionally many of the wounds in the casualty lists included blows to the head from special constable truncheons or bayonets which were used exclusively by the regular infantry.

2: I don't understand the point that's attempting to be made here, first the number of slashing wounds recorded and eye witnesses show that most Hussars seem to have ignored this order. Second, using the flat of blade while very difficult is not a benevolent act. In addition to the conceded dangers of the edge of the sabre, cavalry sabres had weight to them so even if a person is not cut by a blow from a sabre the act of being struck is still highly injurious.

3: Generally speaking the more outspoken reforming MPs tended to be Whigs, and it would be a Whig government that passed the Reform Act of 1832. However this was far from unanimous, much of the opposition to the Six Acts by Whig MPs was less concerned with civil liberties and more motivated by fears of it enflaming insurrection. And the prosecution at the trial of the Peterloo speakers was one James Scarlett a Whig MP.

Footnotes:

1: There is a myth about Waterloo that lays the blame for the violence squarely on the shoulders of the Yeomanry, a volunteer militia while laying praise on the regular military for discipline and restraint. There is strong evidence that individual members of the Hussars and infantry behaved more humanly, Lieutenant Joliffe whose account was very important in exposing the establishments version of events as largely fictitious also contains references to the army attacking and dispersing the crowd.

".. nine out of ten of the sabre wounds were caused by

the Hussars ... however, the far greater amount of injuries were from the

pressure of the routed multitude." Burton Three Accounts of Peterloo 1921

Additionally many of the wounds in the casualty lists included blows to the head from special constable truncheons or bayonets which were used exclusively by the regular infantry.

2: I don't understand the point that's attempting to be made here, first the number of slashing wounds recorded and eye witnesses show that most Hussars seem to have ignored this order. Second, using the flat of blade while very difficult is not a benevolent act. In addition to the conceded dangers of the edge of the sabre, cavalry sabres had weight to them so even if a person is not cut by a blow from a sabre the act of being struck is still highly injurious.

3: Generally speaking the more outspoken reforming MPs tended to be Whigs, and it would be a Whig government that passed the Reform Act of 1832. However this was far from unanimous, much of the opposition to the Six Acts by Whig MPs was less concerned with civil liberties and more motivated by fears of it enflaming insurrection. And the prosecution at the trial of the Peterloo speakers was one James Scarlett a Whig MP.

.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment