The Student Movement in the Shadow of the State

|

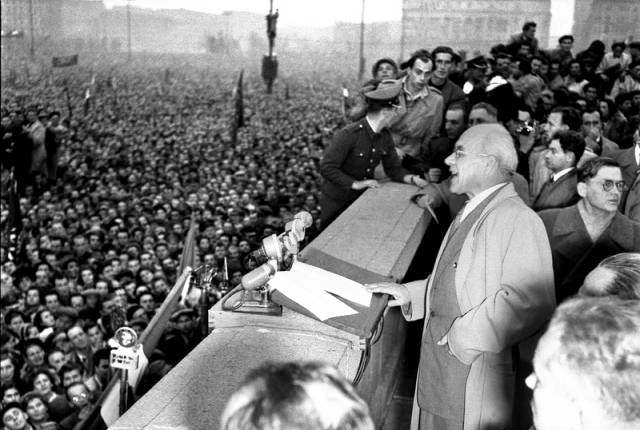

| Władysław Gomułka, speaking to the masses in Warsaw in 1956. During the early days of his rule he was quite popular. However, by the end of the 1960s he had launched anti-Jewish campaigns to silence critics, he was deposed as party leader following popular protests in 1970. |

|

| Edward Gierek (with an unknown interpreter) together with Nicolae Ceausescu, was the communist party leader of Poland from 1970-1980. |

In fact, this "scientific" character was often just an official "cover", a pretext for receiving state grants for "scientific and educational" events on various topics such as peace, the cosmos, Lenin's legacy, etc., for publications and research visits. Although a number of student circles have actually succeeded in researching Esperanto, interlinguistics and international language communication: for example, the University of Warsaw, led by Ryszard Rokicki (second PSEK president), Barbara Jędrzejczyk (later Rokicka) and Jerzy Leyk.

|

| Passport of the Polish People's Republic, photo Jerzy Kuśmider |

|

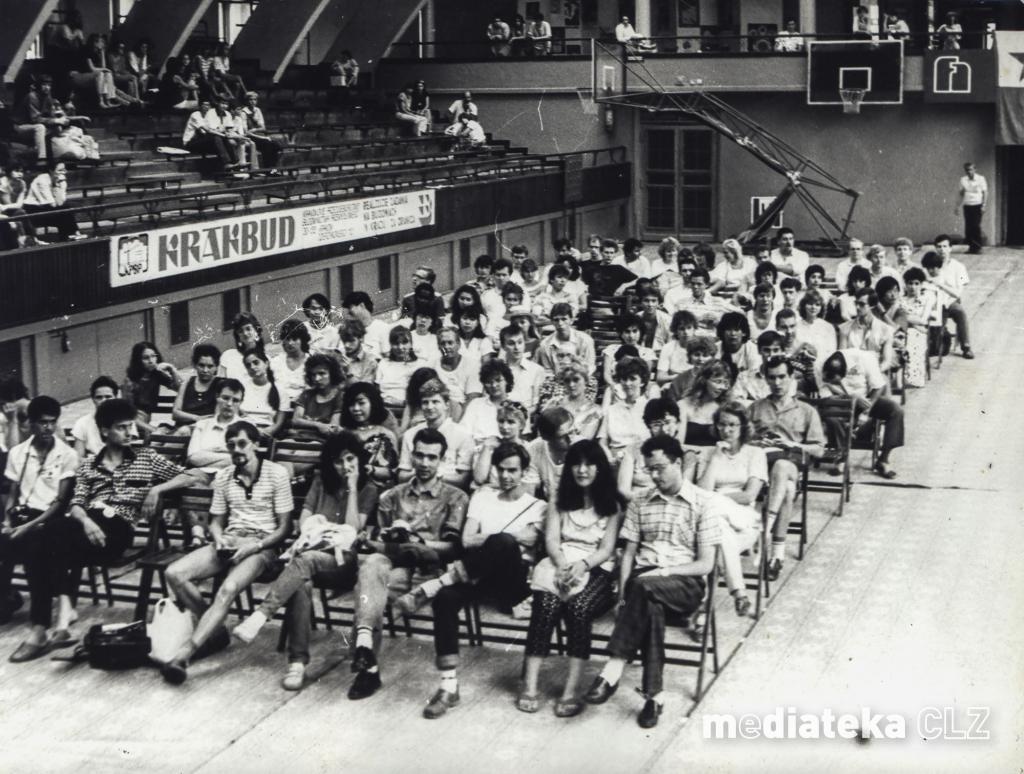

| The International Youth Congress in Krakow, 1987, photo: Mediateko CLZ |

However, I had to have contacts with this service before and during the 43rd IJK in Krakow: I, as PSEK president and LKK vice-president, was responsible for the official invitations of the foreigners and delivered the lists of the guests to the ministry, reported on the program and the congressional publications. Some certainly remember the panic before the IJK inauguration, when the secret agent demanded that I add to the list of participants a 6-person list of the "citizens" of West Berlin who, according to official doctrine, were not citizens of the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), but of a separate "state".

el la Libera Folio English follows Esperanto

La Esperanto-movado dum kelkaj postmilitaj jardekoj estis forta en kelkaj landoj de la tiama sovetia bloko, kaj precipe en Pollando. Esperanto donis ŝancon pri internaciaj kontaktoj eĉ trans la fera kurteno. Samtempe la Esperanto-movado estis uzata de la regantoj por propagando, observata kaj kontrolata de la ŝtato. Jarek Parzyszek rakontas pri siaj spertoj en la pola studenta movado.

Fondita en Zakopane, suda Pollando, en 1972, Pola Studenta Esperanto-Komitato estis sukcesa provo kunordigi la agadon de sendependaj studentaj – edukaj, sciencaj, kulturaj kaj turismaj Esperanto-rondoj kaj kluboj, kiuj funkciadis en multaj polaj universitataj urboj. La organiza kaj financa bazo por la plimulto de la rondoj estis Asocio de Polaj Studentoj (APS).

Studentaj polaj esperantistaj kluboj kaj rondoj ekaperis en la polaj universitatoj post la falo de Bierut-reĝimo (do post 1956). Por poloj, post la morto de Bierut, ŝajnis ke kune kun Właysław Gomułka venis nova, pli bona epoko: aperis novaj revuoj, kelkaj pli frue malpermesitaj autoroj rajtis aperigi siajn librojn aŭ prezenti spektaklojn, oni povis dum kelkaj jaroj publike rememori la rolon de la Landa (subtera) Armeo, multaj intelektuloj rajtis vojaĝi ne nur al Orienta Europo – sed tiu ”libereco” rapide finiĝis.

La plej multaj el la esperantistaj rondoj kunlaboris kun aŭ eĉ fakte funkciis nur danke al APS. En la 60-aj kaj en la 70-aj jaroj granda plimulto de polaj studentoj apartenis al APS, kiu fakte monopoligis la organizan aktivadon de polaj studentoj tiel ke preskaŭ ĉiuj interesgrupoj devis elekti formon de oficiala kunlaboro kun APS. Substrekendas, ke oficiale ne ekzistis aliaj junularaj organizaĵoj. La ŝtato ”zorgis”, ke la junularaj organizaĵoj ne fordrivu en ”malĝusta” direkto.

Krom la departemento pri junularo en la Centra Komitato de la komunista partio (Pola Ununiĝinta Laborista Partio), gvidata de aparta sekretario pri la “ĝusta” direkto de junulara aktivado, zorgis financaj ŝtatoservoj dividantaj subvenciojn, pasportoservoj donantaj permesojn (“pruntantaj” pasportojn) por vojaĝi, cenzur-oficejoj: centra en Varsovio kaj vojevodiaj, polico (nomata milicja) kaj sekretaj ŝtataj servoj, kun miloj da sekretaj kunlaborantoj, kiuj raportadis pri diversaj kampoj de socia aktivado.

La kontrolado okazadis ankaŭ oficiale, interne de la unuopaj organizaĵoj lok- kaj landnivele.

El mia preskaŭ 10-jara sperto de Esperanto-aktivado en Pola Popola Respubliko mi praktike scias ke la pola Esperanto-movado, precipe la studenta, estis observata kaj kontrolata de la ŝtato.

Kompreneble ne nur polaj studentoj-esperantistoj estis observataj kaj kontrolataj ‒ tute kontraŭe. Dum la 1980-aj (kaj ŝajne ankau dum la 1970-aj) jaroj Pollando estis ”la plej libera” inter la socialismaj landoj. Dum kaj post la ”milita stato” (1981-84) niaj amikoj el GDR, Sovetunio, Bulgario, Rumanio, Ĉeĥoslovakio, timis aŭ ne povis viziti Pollandon, escepte de nombre limigitaj grupoj, organizitaj de Komsomol, FDJ kaj tiel plu.

Pola Studenta Esperanto-Komitato neniam estis sendependa organizaĵo, ĝi fakte eĉ ne estis organizaĵo laŭ jura vidpunkto. Ĝi estis centra reprezentantaro de polaj studentoj-esperantistoj, konsistanta el po unu reprezentanto de ĉiu funkcianta studenta rondo/klubo. Ĉar la plej multaj studentaj Esperanto-rondoj kaj kluboj havis en sia nomo la vorton ”scienca”, PSEK funkciis ĉe la Scienca Komisiono de la Ĉefa Konsilio de Asocio de Polaj Studentoj.

Fakte tiu ”scienca” karaktero estis plej ofte nur oficiala ”nomkovraĵo”, preteksto por ricevadi ŝtatajn subvenciojn por ”sciencaj kaj edukaj” aranĝoj pri diversaj temoj kiel paco, Kosmo, Lenin-heredaĵo ktp., por eldonaĵoj kaj esplorvizitoj. Fakte kelkaj studentaj rondoj efektive sukcesis sciencigi la esploradon pri Esperanto, interlingvistiko kaj internacia lingva komunikado: ekzemple tiu de la varsovia universitato, gvidata interalie de Ryszard Rokicki (la dua PSEK-prezidanto), Barbara Jędrzejczyk (poste Rokicka) kaj Jerzy Leyk.

La varsovianoj jam komence de la 70-aj jaroj okazigadis Sciencajn Interlingvistikajn Seminariojn (poste: Simpoziojn). Grandsukcesaj SIS-oj en la 80-aj jaroj estis aranĝitaj de Akademia Centro Interlingvistika, funkcianta ĉe PSEK, ariganta PSEK-eksaktivulojn, kiu eldonadis postsimpoziajn materialojn kaj apartajn interlingvistikajn kajerojn. La ĉefmotoroj de ACI estis Barbara kaj Ryszard Rokicki.

Dua centro estis la studenta scienca rondo en la urbo Łódź, kiu, kunlabore kun APS, organizis ĉe la Lodza Universitato internaciajn konferencojn pri internacia lingva komunikado, eldonante riĉenhavajn postkonferencajn materialojn dulingve. La ĉefa motoro de tiuj konferencoj estis la kvara PSEK-prezidanto Tadeusz Ejsmont, kiu en 1982 doktoriĝis pri Esperanto ĉe la Lodza Universitato. El Lodzo venis kaj tie vivas la unua PSEK-prezidanto (dum du oficperiodoj), Władysław Stec.

PSEK aktivadis ne nur sciencterene, sed ankaŭ kulture. Jam antaŭ la PSEK-epoko, helpe de Asocio de Polaj Studentoj, Marek Pietrzak fondis en 1958 Polan Esperanto-Junularon, kaj li longe redaktis la kulturan-edukan revuon TAMEN, eldonatan unue en Toruń (1959-60), poste en Vroclavo (1960-64) kaj fine en Varsovio (1965-67). Fine de la 80-aj kaj komence de la 90-aj jaroj de PSEK estis eldonata Studenta Gazeto, kiun ĉefredaktis Jarosław Miklasz el Bydgoszcz kaj en la redaktoteamo kunlaboris i.a. Krzysztof Łobacz, Elżbieta Malik kaj Jarosław Parzyszek.

Sukcesojn kulturkampe kultivis PSEK-filoj: Esperanta Kultura Societo en Poznań (fondita de Paweł Janowczyk, Zbigniew Kornicki, Andrzej Naglak, Alicja Lech kaj daŭrigata de Leszek Lewandowski) kaj en Zielona Góra ĝis 1992 Kooperativo Verda Monto, gvidata de Jerzy Rządzki, kiu pli frue fondis kaj gvidis Studentan Esperanto-Teatron kaj okazigadis en kaj apud Zielona Góra teatro- kaj kulturfestivalojn. En tiu teatro la ĉefrolojn plenumis interalie Dorota Świerstok (nun Polaczek), Mira Rządzka, Leszek Lewandowski kaj Anna Szumska (nun Hanna Szczęsna).

Esperanto-Kultura Societo dum kelkaj jaroj kunlaboris kun la Kultura Komisiono de APS eldonante kelkajn interesajn volumetojn, ekzemple la poemkolekton Mi estas nur virino de Anna Świrszczyńska en traduko de Tomasz Chmielik, Doktryna Zamenhofa de Jarosław Parzyszek kaj Esperanto i nauka de d-ro Leszek Kordylewski.

La ĉefa inspiro de PSEK tamen estis nek scienco nek kulturo, sed vojaĝoj. Dank’ al la APS-ombrelo PSEK-delegitoj amase vojaĝadis al internaciaj Esperanto-aranĝoj, ĉefe en Eŭropo sed ne nur, ekzemple en 1981 al Brazilo kaj en 1986 al la israela IJK en Neurim veturis 4 PSEK-reprezentantoj. Tiaj eksterlandaj vojaĝoj estis multe pli komplikaj kaj finance nepageblaj por PEJ-anoj, pro tio ofte PSEK-anoj reprezentis Pollandon en TEJO-Komitato kaj foje eĉ estis TEJO-estraranoj (Jan Koszmaluk, Jarosław Parzyszek).

En la Pola Popola Respubliko ekzistis tri kategorioj de pasportoj, kiuj tiam ne estis propraĵo de la civitanoj sed de la ŝtato, kaj la ŝtato povis afable permesi al siaj civitanoj pruntepreni pasporton por vojaĝi eksterlanden. En la Centra Oficejo de APS, ĉe la strato Ordynacka 9 en Varsovio, funkciis pasporto-deponejo kun rekta kontakto kun la Ministerio pri Internaj Aferoj.

Por oficala vojaĝo oni ricevis duonprivatan pasporton (kun la litero ”B”), kiu ebligis vojaĝi nur al socialismaj landoj, aŭ kun speciala stampo rajtigis vojaĝi al ĉiuj ŝtatoj de la mondo. La Pasporta Deponejo de APS helpis ankaŭ ricevi vizojn al t.n. kapitalismaj landoj.

Ankaŭ la lokaj (vojevodiaj) pasportoficejoj “pruntis” pasportojn al studentoj-esperantistoj, surbaze de la oficialaj invitleteroj kun aldonaj rekomendoleteroj sur la oficiala papero de Asocio de Polaj Studentoj. Oni povis kaj foje sukcesis ricevi pasporton sen tia letero, sed tiu vojo kutime estis pli longdaŭra kaj necerta.

La PSEK-delegitoj devis post la oficialaj vizitoj verki kaj rapide liveri al APS oficialajn raportojn. Parto de la raportoj, eble eĉ ĉiuj, estis plusendataj al la ministerio pri internaj aferoj aŭ/kaj ties lokaj oficejoj. Foje, krom la ”oficiala” (formale publika) raporto la delegitoj estis petataj pri apartaj, sekretaj raportoj.

Ekzemple en 1986 de mi, tiama prezidanto de PSEK kaj estrarano de TEJO, invitita partopreni TEJO/KER Seminarion en la Eŭropa Junulara Centro en Strasburgo, oni ‒ funkciulo de sekreta servo ‒ postulis apartan raporton pri la neoficialaj okazaĵoj kaj interparoloj en Strasburgo. Tiam, timante la postsekvojn, mi rifuzis prepari tian raporton kaj finfine ne veturis al la seminario, sed Pollandon reprezentis du aliaj homoj.

Kun tiu servo mi tamen devis havi kontaktojn antaŭ kaj dum la 43-a IJK en Krakovo: mi, kiel PSEK-prezidanto kaj LKK-vicprezidanto respondecis pri la oficialaj invitoj de la eksterlandanoj kaj liveradis la listojn de la invititoj al la ministerio, krome mi raportis pri la programo kaj la kongresaj eldonaĵoj. Kelkaj certe memoras la panikon antaŭ la IJK-inaŭguro, kiam la sekreta agento postulis de mi aldoni al la kongreslibra listo de la partoprenantoj 6-personan liston de la “civitanoj” de Okcidenta Berlino, kiuj laŭ la oficiala doktrino ne estis civitanoj de la Federacia Respubliko Germanio, sed de aparta “ŝtato”.

Poste kune kun kelkaj LKK-anoj ni kolektis la kontraŭreĝimajn foliojn kiujn, dum la ekskursotago de la Krakova IJK, disĵetis unu el la polaj IJK-partoprenantoj.

Ni, mi kaj kelkaj aliaj LKK-anoj, sciis ke en la IJK-kongresejo (la sporthalo de Wisła) en Krakovo la kongreson de supre, senĉese observadis kelkaj sekretaj funkciuloj. Unu el tiuj funkciuloj kontaktis min ankaǔ dum la 72-a UK en Varsovio, kie mi respondecis pri la junualara programo. Lin interesis ne la UK-programo sed la neoficialaj interparoloj.

La plej granda sekreto de

la internacia aktivado kaj sukcesoj de PSEK estis la t.n. persontaga,

sendeviza interŝanĝo, kio signifis ke partopreno de unu eksterlandano

dum unu tago de PSEK-aranĝo egalis al la partopreno de unu PSEK-ano en

eksterlanda aranĝo. Ni havis multajn partnerojn de tiaj interŝanĝoj. La

plej grava kaj la plej ofte uzata estis la PSEK/GEJ kontrakto, sed ni

havis apartajn kontraktojn kun: TEJO, JEFO, JES, JEB, ĈEJ, BEJ, HEJ, NEJ

kaj KCE en Svislando.

La plej granda sekreto de

la internacia aktivado kaj sukcesoj de PSEK estis la t.n. persontaga,

sendeviza interŝanĝo, kio signifis ke partopreno de unu eksterlandano

dum unu tago de PSEK-aranĝo egalis al la partopreno de unu PSEK-ano en

eksterlanda aranĝo. Ni havis multajn partnerojn de tiaj interŝanĝoj. La

plej grava kaj la plej ofte uzata estis la PSEK/GEJ kontrakto, sed ni

havis apartajn kontraktojn kun: TEJO, JEFO, JES, JEB, ĈEJ, BEJ, HEJ, NEJ

kaj KCE en Svislando.

La internacia historio de PSEK finiĝis post la falo de la Pola Popola Respubliko. Unue, pro la ekonomia krizo, la nekomunista registaro de Mazowiecki/Balcerowicz preskaŭ komplete nuligis la ŝtatajn subvenciojn, due la civitanoj ricevis la rajton libere vojaĝi kaj finfine fariĝis posedantoj de pasportoj por la tuta mondo, trie niaj Esperanto-partneroj nuligis la kontraktojn pri la sendeviza interŝanĝo.

En 1992 en Gdańsk okazis la 14-a Studenta Somera Esperanto-Renkonto (la unuaj 12 SER okazadis en Toruń) kaj la jubilea seminario kaj balo de PSEK, kiun organizis la lasta PSEK-prezidanto, Adam Cholewiński, kaj partoprenis interalie la unua PSEK-prezidanto Władysław Stec kaj mi. Laŭ mia scio tiu estis la lasta aranĝo kaj la fino de la PSEK-historio.

Iom postvivas PSEK pere de ARKONES – Artaj Konfrontoj en Esperanto, kiu unafoje okazis en 1979 en Poznań.

Jarek Parzyszek

.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment