So, I'm not a fanatic follower of Karl Marx, and I'd go so far as to say I find the actions of many Marxists to be embarrassing and rather annoying and counterproductive. One example of this is the use of Marx as a flesh and blood bible. Much of socialist discourse is really just a petty game of idol worship and quotation fighting, and like most Christians many Marxists are fond of just taking random snippets of gospel and using them because they look like they're agreeing with a preconceived idea if you just give them a quick glance and don't bother reading the rest of the text or the historical context.

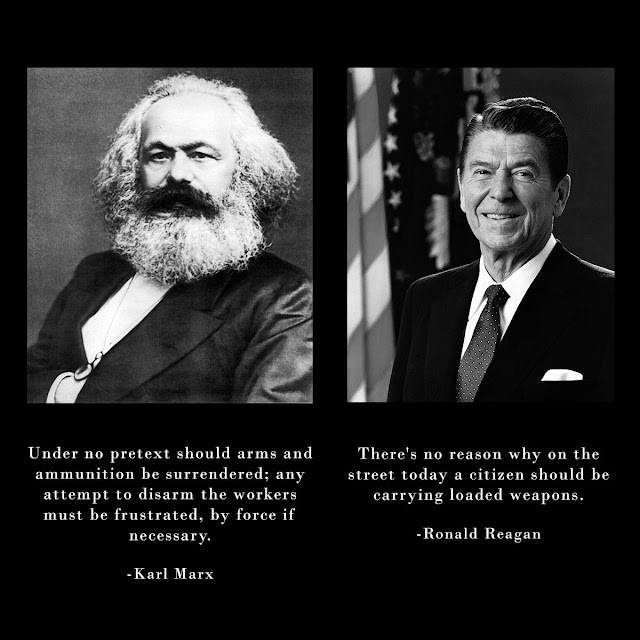

A big example of this is 2nd Amendment Marx, you've probably seen the famous quote or a paraphrasing of it "Under no pretext should arms and ammunition be surrendered; any attempt to disarm the workers must be frustrated, by force if necessary." Had Karl Marx been an American politician alive today or some point in the 20th Century, I would also assume he's weighing in on America's gun control debate. But he wasn't. What he was actually doing was commenting on the political situation in Europe in the middle of the 19th Century.

That quotation comes from text written in 1850 Address of the Central Committee of the Communist League. The text is an attempt by Marx and Engels to promote a new strategy in the aftermath of the 1848 wave of Revolutions. To be specific, this is the rest of the paragraph that the above sentence comes from

2. To be able forcefully and threateningly to oppose this party, whose betrayal of the workers will begin with the very first hour of victory, the workers must be armed and organized. The whole proletariat must be armed at once with muskets, rifles, cannon and ammunition, and the revival of the old-style citizens’ militia, directed against the workers, must be opposed. Where the formation of this militia cannot be prevented, the workers must try to organize themselves independently as a proletarian guard, with elected leaders and with their own elected general staff; they must try to place themselves not under the orders of the state authority but of the revolutionary local councils set up by the workers. Where the workers are employed by the state, they must arm and organize themselves into special corps with elected leaders, or as a part of the proletarian guard. Under no pretext should arms and ammunition be surrendered; any attempt to disarm the workers must be frustrated, by force if necessary. The destruction of the bourgeois democrats’ influence over the workers, and the enforcement of conditions which will compromise the rule of bourgeois democracy, which is for the moment inevitable, and make it as difficult as possible – these are the main points which the proletariat and therefore the League must keep in mind during and after the approaching uprising.

He's talking about a future military force acting in a hypothetical revolutionary situation. In the text this scenario is called inevitable, but it didn't happen, so it wasn't. I'm not really surprised the 1850 Address isn't well known, and its legacy is this one sentence, it's referring to a period that was unique or at least hasn't been repeated, and a lot of its immediate predictions didn't pan out, and ultimately Marx and Engels would soon move away from the strategy it promotes.

During the early 19th century, there was a continental wide explosion in the popularity of militias of one type or another. Some like the Yeomanry of England were established by men of property and their sons to be a supporting force for the professional army, as was the case in the Peterloo massacre. Others were more plural bodies of the citizenry and were supposed to assist the nation in times of strive, and there were also more radical and less official bodies made up of working men.

|

| Compare: Above the Yeomanry at Peterloo, and below the more popular and insurrectionary militia at Prague, 1848. |

This movement was in response to general conditions and developments, rather than the strategy of any would be leaders of the workers. The nobles and industrialists and landowners grew worried that the professional forces of law and order were incapable of offering sufficient protection from rebellious peasants and workers, so funded and established their own bodies of armed men. The growing national movements of professional politicians and thinkers felt that the professional armies which were still in the hands of a powerful King or noble class were not truly representatives of the nation, and so agitated for the creation of citizens and national militias to form a truly patriotic force. Meanwhile, more radical elements amongst the workers and student fraternities also promoted the establishment of armed bodies, both to play a role in some expected insurrection and to act as a counterweight to the violence of the authorities. There was also a Liberal utopian case for the militia system at the time, it was argued that militias were sufficient to protect life, liberty and property at home, and man the city walls and "natural" borders in time of crisis, but weren't suited for offensive action, so by adopting the militia and replacing or at least heavily reducing professional armies, the militia could be the seed for greater international peace.

A key issue among the pre-1848 German liberal opposition to the existing order was the reduction if not the abolition of princely standing armies and their replacement by militias based on universal male military service (also see entry under Military Reform). Their models were the 1793 French levee en masse, an idealized memory of the halcyon days of the Prussian Landwehr during the 1813 war of liberation or the local municipal civil guards of self-governing towns. What these shared was a stress on a non-professional armed force of citizens serving only in times of emergency. Liberals generally associated standing armies with wars of aggression and believed that militias could only be used for defense. A Europe of militias would be at peace.

For years, this grew into a very heterodox movement of militias in many European nations, until in 1848 when the situation exploded into mass revolts in France, the German states, the Italian states, and the Habsburg Empire including in Prague, Hungary and Vienna. The 1848 Revolutions were a chaotic mix of participants and ideologies, liberalism, republicanism, democracy, nationalism, and to an extent early socialism played its part in motivating and shaping the struggles.

It's difficult to untangle, but in general terms, and I must stress general, the militias that were composed mainly of the affluent and the gentry sided with the reactionary governments, while those with a more popular and working class composition tended to side with the more radical forces.

For example, the French National Guard in Paris:

In February 1848, the Paris National Guard's some 50,000 members were divided into twelve legions, one for each of the city's arrondissements. The legions, in turn, were broken down into battalions, recruited at the level of the quartiers of each arrondissment. The legions were commanded by colonels or lieutenant-colonels, the battalions by majors, captains, and sometimes lieutenants. Of the city's twelve National Guard legions, only one, the first, from the notoriously haute bourgeois Champs Elysée-Place Vendôme district, would prove loyal to the monarchy at the onset of the February revolution. The mass defection of the guard has been seen by many historians as the crucial event in the collapse of the Orleanist regime. Georges Duveau contended that "the insurrection [of the February 1848] could have been brought under control if the National Guard had remained loyal to the system." He added that the morale of the regular army plummeted when the troops "realized that [they] were liable to be struck in the back by the National Guard."

The French National Guard - Bruce Vandervort

Though there were exceptions, in Hungary the Habsburg Emperor faced a revolt led by Hungarian nobles and was able to win support from the serfs by promising to abolish serfdom, while the nobles didn't offer them much of anything. While the insurrectionary wave was a sustained challenge to the established authorities and did force a number of political concessions like the abolition of serfdom in the Habsburg Empire, the wave was defeated with the powers of Europe remaining intact if shaken and bruised. As a result the widespread popularity for the people armed, and militias greatly declined amongst the liberals and the conservatives, and there were moves to control and disarm the surviving radical armed bodies, though a minority of them remained in existence for a while yet.

The address of 1850 was a response to this aftermath, this is why it talks about a "proletarian guard" and opposition to the revival of the "citizens" militia movement. There were still some armed workers groups, many workers had been armed and experience combat and the storing and use of weapons, and the idea that workers could form armed guards and fighting forces was a recent memory. He wasn't talking about an unrestricted market in guns for the consumer, which exists in the USA of today. Most of those arms held by people in the famous paintings of barricade fighting were bought clandestinely or seized from the state armouries for what its worth.

But does it really matter? Well it's dishonest and adds to the general confusion which is a problem, but there is a much more serious problem with taking Marx out of context to weigh in on the American gun culture debate. That is, the American worker is already disarmed. The workers were armed in the 1800s through several forces hundreds or even thousands strong, and were actively training themselves in combat techniques. The American working class is not armed because a plumber can afford to have a small collection of generic (or "civilian" as Americans call them) rifles, nor because a UPS delivery driver can save up to buy a small revolver. Even if a greater proportion of the more dangerous weapons were bought by Americans on lower incomes this wouldn't change anything.

I used to own a gun and know several people who work for a living and still have some, no one would be taken seriously claiming the working class of the UK is armed and should resist attempts to disarm them.

The American class is not armed and in danger of being disarmed, that's not what the gun control debate is about. What America does have is a relatively unrestricted market for firearms, with one political group wishing to push for more restrictions on commercial transactions while the other side is pushing for even fewer. What militia movement North America does have is a scattering of ill-disciplined far right fanatics anticipating and longing for a sort of apocalyptic race war. If anything, they're more reactionary than the most reactionary elements in Europe in the 1850s.

The two just aren't comparable, if anything I believe the laissez-faire gun market that exists in the modern United States is evidence of the lack of such a presence. There was a period of time when the class struggle in the US was extremely violent with essentially smaller re-enactments of the Civil war breaking out, in the mining towns of the South west and the Appalachians, but after the battle of Blair Mountain and the end of the 1920s armed working men getting into stand-offs with the company security, and the police, and the national guard gradually faded. When the spectre of radical armed insurgency reared its head, as shown by the Black Panther Party, the response was Reagan's gun control measures for the state of California. The New Left of the 60s and 70s did see isolated pockets of armed resistance, but these were quickly and brutally isolated and neutralised by the 1980s.

So I don't think it's particularly wise to put the cart before the horse and try to will a revolutionary army into existence. The only way I see that leading is in a new form of Foquismo which only really works in conflict as depicted by video games. If American revolutionists really wish to live up to this scarecrow of Marx, then they'll have to put a lot more work in, I'm aware there are now several active gun clubs, it's not on the same scale as the militia columns, but hopefully if nothing else they're raising the standards of gun safety and discipline. Possibly they could be the foundations for a more substantial force, assuming that is even something desirable or viable, but we'll have to wait and see.

.jpeg)