Search This Blog

Wednesday 26 February 2020

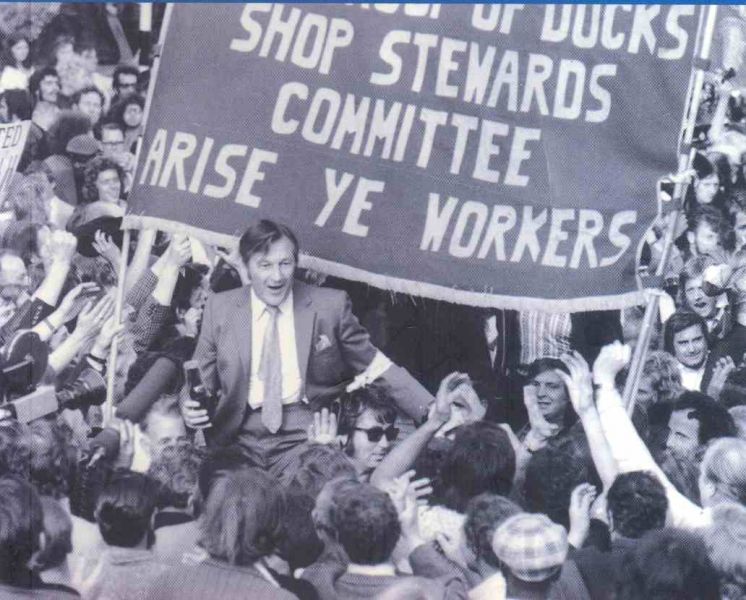

1972: Dockworkers Strike

1972 was a big year for strikes and labour unrest in the UK. Famously the Miners strike of 1972, seen as a opening fight in the big conflict between the Miners and the government in 1974, which lead to the defeat of Ted Heath. But there was also a serious builders strike which involved a young Ricky Tomlinson who was one of the Shrewsbury 2, arrested for picketing. Residents of Kirkby held a massive rent strike in the same year.

And there was a nation wide strike of dockers. The strike was motivated by growing government interference in labour disputes with its new legislation on union activities, planned redundancies after the container revolution and other technological improvements meant employers felt confident they could pay fewer people to do more work, and the growing monopolisation of the shipping industry.

Cinema Action made a short documentary on the picket lines of the strike and its very interesting. Trade Unions in Britain have a reputation of being extremely conservative and sluggish, so it was surprising to see a strike organised mostly by the shop stewards that pushed the bureaucracy much further than they wanted to go. And we hear many striking dockers denounce capitalism, how capitalism uses technological progress purely to increase profits instead of as means to improve conditions and lives of everyone.

And several dockers outline how the attitudes of both Labour and Conservative governments to the industry and the dock workers isn't particularly different. Labour governments have also a pretty dark track record of handling disputes in that industry.

"We've got this tremendous struggle by the employing class, for the survival of their profits. And that means they're going to intensify the struggle against the working class in order to maintain their profits. Anybody that advocates going along with the law as a kind of a tactic and wait for a general election so that the next government can repeal it, is just ignoring history.

Because the law we've got today is just a reflection of all the governments we've ever had in the past, every government that we've ever had in Britain has been a government that has tried to anchor off the working class in one way or the other. It happens to be a Tory government this time, the last one was a Labour government who laid the blue print for it.

And unless we can return to the masses, to the workshop floor, that the workers themselves who are working there every day of the week, clocking on, clocking off. Getting a pittance for the work that they do for the employers. Unless we can get that in our own head, that we can fight this battle and win. Then we'll lose."

Link https://youtu.be/qQGnKf58fkg

Thursday 13 February 2020

Loving and Raging

I've been reading bits and pieces from the defunct US Anarchist group Love & Rage (LR), going back through the archives of dead groups is a bit disjointed usually and so the quality of the content can vary quite a bit. I've read some terrible stuff, some very interesting stuff and some are a weird combination of the two. The one text that was put out by a member of LR that seemed to be everywhere stuff like this can be found and had developed a reputation, its by a fellow called Chris Day, it was published in 1996 and it has a provocative title The Historical Failure of Anarchism.

Several American activists have recommended this to me over the years so I know its remained current to a degree, and every time I've read it in the past I was confused at what was so great about it.

I figured it might be time to give it another try, since I wasn't a major fan of the other LR content overall.

I still don't see what is so compelling about the document to be honest. If anything I'm even more critical of it than I was originally, because in addition to not agreeing with many of Day's arguments, I now have a lot more knowledge of the examples he's using and have come to the realisation that he is at times very sloppy, and quite selective with them. I go so far as to say that all of the events he uses as a case study, namely the revolutions in China, Spain and Ukraine if looked at beyond Day's very narrow and self serving accounts of them severely undermine his main thesis.

Speaking of the main thesis, the argument Day is making is that Anarchism has failed, and yes in 1996 there were no examples of successful anarchist revolutions. The issue here is that no one outside the status quo has succeeded either. So this seems less an issue for the Anarchists in particular and more an issue for every person and tendency whom opposes the capitalist system to grapple with.

Bizarrely Day doesn't agree, for example this passage.

The consequence of this is to blind ourselves to the counter-revolutionary elements in anarchist theory and practice and the legitimate accomplishments of many marxists (or other "authoritarian" currents).

In opposition to this mechanical or scholastic approach I believe we should look at the whole experience of the revolutionary movement dialectically. We need to identify the aspects of anarchism that effectively crippled it as a credible revolutionary alternative to marxism. We need to examine when and how liberatory currents asserted themselves within Marxism.

What legitimate accomplishments? and what way is Marxism as Day understands it a credible revolutionary movement? Could you in 1996 point to a single successful Marxist revolution? The answer is no. Some Maoists and Stalinists would argue the point from the 1950s-80s. But calling the Eastern bloc and the PRC et al successful Marxist revolutions is quite a stretch. It would only work if you assume the Bolsheviks and Communist Party of China (CPC) etc were liars from the beginning and they were aiming to build the Soviet Union into what it became from day one. If on the other hand if you take them at their word and give them the benefit of the doubt that their intentions of building a new socialist society was genuine, you have to conclude that these projects are also failures.

I can see how someone in the Cold War period could be impressed by the sheer size and power of the Eastern Bloc and the People's Liberation Army, and be taken in by it. But Day wrote this in 1996, when the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc had collapsed, the PRC and Vietnam and Laos were rushing to integrate into the global economy, and Cuba was near collapse, Yugoslavia had torn itself apart in a nationalist bloodbath, Albania was in the middle of a insurrection and North Korea was being ripped apart by famine. So I have a hard time seeing what Day is getting at with his comparisons.

Indeed, later on by his own admission the only successful revolutions Day can point to have been nationalist and often state capitalist. So the question refuses to go away, if Day's thesis is correct then the only realistic alternative is for everyone to pack up and start supporting nationalism. Or I suppose just give up and let everything take care of its self.

But no this is not what Day wants, Day is trying to argue for a new revolutionary movement, one that can rise to the challenge, and has sketched out some basic requirements. Such as the ability to compromise.

Revolutionary situations do not present themselves to us only after we have made perfect preparations for them. They arise suddenly when the old order is unable to maintain its rule. It would be irresponsible in such situations not to try to carry out a thorough libertarian social revolution. But it isn't necessarily the case that it is always actually possible to win everything we want. In this case the revolution will be confronted with choosing between different kinds of compromises or half-measures in order to "survive."

In Ukraine many of the Anarchist groups including the Insurgent Army worked with the Bolshevik red army. This enabled the army to gain footholds in Ukraine and buy time to build up its forces to attack and destroy the Anarchist organisations and conquer the territory.

Even the example of China shows the dangers of this approach. The CPC initially formed a military and political alliance with the Nationalist party the KMT, during the 20s when Chiang Kai-Shek began a northern expedition to take on the warlords and march on Shanghai the CPC supported these efforts.

The most well known example was in Shanghai, as the KMT army approached, there was a general strike which quickly escalated into an uprising with many of the factories under the control of the workers and militias and armed patrols moving into the streets. The KMT army remained on the outskirts and pressured the CPC to intervene and talk the workers into disarming. The Shanghai workers listened and disarmed and welcomed the KMT army in. The KMT would massacre thousands of CPC members and suspected revolutionary workers. This was the start of a general campaign by the KMT against the CPC and succeeded in destroying their branches in the towns and cities. Surviving members including Mao Zedong had to flee into the countryside and link up with its small rural organisation and its poorly equipped militia.

In place of these examples of revolutionaries making compromises that destroyed them, what counter examples of compromises leading to survival does Day provide? None. There is nothing here, a surprisingly large number of Day's proposed alternatives are based on nothing.

And following on from this in the section on unequal development where Day spends a lot of time talking about China the issues with Day's honesty become more apparent.

Day clearly knows a lot about the Chinese revolution, so its when Day starts talking at length about it that I feel confident that this isn't the case of limited knowledge but deliberate misrepresentation. The whole section is full of half truths and distortions, so I'll just select a few.

Simply put this is a lie, I don't believe a person could study the history of the Chinese revolution and completely overlook the 1920s when the Chinese industrial proletariat did in fact take matters into its own hands. The Shanghai insurrection is the most well known incident of this since its hard to bury the murder of 20,000 in an international port city. But it isn't the only one, in 1925 there was a general strike throughout much of China's industrial cities, though strongest in Shanghai, Canton and Hong Kong. Initially the strike wave which also saw the establishment of assistance programs, organised pickets, was focussed on foreign owned business and a boycott of British (produced in Chinese factories) goods, but expanded to include all of the colonial powers and then targeted Chinese manufacturers too.

The Chinese Revolution must be understood in this context. It was overwhelmingly a peasant revolution that destroyed a very rotten old system, redistributed the land, and established China's relative economic independence from imperialist domination. Only once these fundamental tasks had been carried out did it even become possible for the Chinese Communist Party to talk about what to do with China's puny capitalist sector. The cities had been controlled by the Kuomintang and the only significantly industrialized region, Manchuria, had been under Japanese control. The industrial proletariat, such as it was, did not have either the experience or the organization to take matters into their own hands. Any move to do so would need the active support if not of the peasantry, then of the Communist Party.

The strike lasted for months until Chiang Kai-Shek launched a coup within the KMT and raided the Canton-Hong Kong strike committee. Indeed the period from 1919-26 shows that Chinese workers were very militant, the main stumbling block to them "taking matters into their own hands" was often the physical repression of the colonial forces, the warlords and the KMT, and the CPCs constant need to reorient itself with the KMT. The CPC was able to build a union federation of 500,000 members for a time before it was driven underground, and May Day celebrations were often well attended.

But acknowledging that the Chinese industrial workers were politically active but kept under the thumb of powerful forces would undermine Day's argument about the Chinese revolution. He'd also have to explain why once the CPC started surrounding and taking over industrial towns before final victory they did not support working class activity.

Furthermore the description of the power relationships between the peasantry and the CPC is bizarre and misleading.

There was no peasant revolution in territory controlled by the CPC prior to their victory in 1949. On the contrary the CPC relied on the support of local land lords and actively discouraged attempts by peasants to enact land reforms. They had to make do with CPC cadre mediations and some rent reductions. When land reforms did occur it was under the direct oversite of the CPC officials. This is why land redistribution was so contradictory in China, at first the big estates were broken up and land parcelled out, then in the 1950s all of a sudden the land was redistributed again and collectivised by the rural cadres to establish a commune system.

But the question wasn't simply one of running the existing enterprises, it was one of dramatically and immediately expanding the industrial base to forestall famine and for that the expertise of the tiny capitalist class was indispensable.If you're wondering no Day doesn't mention the famine that resulted from the Great Leap Forward industrialisation program. This is why his writing on China is essentially worthless, he's deliberately ignoring massive issues with his reading of the Chinese revolution in order to mislead the audience.

The next section is called "Anarchism in one country" where Day argues the impossibility of building an anarchist society within the borders of one country. I wasn't aware this was an idea proposed in anarchist circles or a "dogma" that needed combatting. And since Day doesn't quote or mention anyone proposing such a scenario I can only conclude it wasn't. I think the only purpose of this section is to lay the groundwork for the next one about the need for a revolutionary army, since the last half of the one country section is also about that.

This Revolutionary Army section is the closet Day goes to suggesting an alternative to the dogmatic anarchism he's criticising. And its also one of the weakest sections because Day doesn't explain what a revolutionary army is. Instead he defines as different from a Spanish militia, and cites a book by John Ellis "Armies in Revolution" and the Insurgent Army of the Ukraine and the People's Liberation Army(PLA). The problem with this is that is muddled, the Insurgent Army and the People's Liberation Army were nothing alike so we can't generalise from that.

Instead what we get is more distortions to make the argument seem more compelling than it is.

The militias, at least initially, were the picture of decentralism and non-authoritarianism. And the military consequences were disastrous. Anarchist accounts of the operations of the militias heavily overemphasize their occasional heroic victories and minimize their frequent defeats or simply blame them on the refusal of other forces to provide them with the arms they needed.This isn't true, the militia's were initially very sucessful, they pushed out the rebelling army in the cities, which involved heavy street fighting and the storming of barracks which were fortresses. In Barcelona alone General Goded was in command of 40,000 troops, the workers of Barcelona drove his forces out of the city and captured him, he was tried and executed in August of 1936. They were also successful on pushing into Aragon and liberating many villages from the army and the local Falange and Civil Guards. There wouldn't have been a revolution without them.

And yes the refusal of arms was a major factor in many engagements. During the purges, Communist party members who overruled the party ban on support for the POUM were imprisoned and shot.

I know nothing about Chris Day but his constant dismissal of logistics as "excuses" tells me he isn't a military expert. A military organisation is a hungry organisation. Artillery and bullets don't come out of thin air.

For an example the CNTs offensive to take the town of Sietamo.

Even so, supplies for a campaign in the rural regions were ridiculously inadequate: no artillery, no machine guns, no trucks. When on my first contact with the militia on the outskirts of the town of Sietamo I saw the poverty of their equipment my heart sank in my shoes. How could these men in overalls and canvas slippers expect to halt the drive that would certainly be coming from the direction of Saragossa? Thoughts of Ethiopia flitted through my mind. Men were lying about in all attitudes alongside a rural road, sleeping, eating, discussing what was to be done. Hundreds of farmers from the surrounding districts had joined them. They wanted to enlist. But there were no rifles to hand out. Three planes zoomed overhead and dropped their bombs on the railroad tracks and on the orchards. A wheat field had caught fire. Fragments of high explosives clattered on the barn roofs. Machine-gun bullets pecked away at the plaster walls of the cottages. One group of milicianos sat about under an umbrella tree staring somberly at the evolutions of the metal birds in the sky. One pursuit plane veered around and almost touched the roofs of the houses and rattled its death spray. The machine flew so low I could see the observer swing his machine gun around.(In Barcelona. Meeting with Durruti and the taking of Sietamo – Pierre van Paassen)

http://libcom.org/history/barcelona-meeting-durruti-taking-sietamo-–-pierre-van-paassen

Coordination and sectarianism between the groups was an issue, but it was exacerbated by the Communist party and the advisers from the Soviet Union, and did improve between many of the other groups in the CNT, UGT, POUM.

Were the militias perfect? No. Could they have been improved? Yes. Do Anarchists romanticise them? Some do yes. But that isn't unique to them, I would argue this document shows Day romanticises the PLA.

Could a revolutionary army do better? Well we have no way of knowing, nor does Day provide a convincing argument for how.

In this process crucial time was often wasted and military opportunities lost. When coordinated actions were carried out the modified plans were often greatly reduced in scale, often to the point of making them irrelevant. Militias jealously refused to share materiel with each other. Observers of all perspectives noted how militias of each organization took a certain delight in the defeats suffered by the militias of other organizations.This are problems, but they aren't remotely unique to militias, they're endemic to all military forces. The Soviet army just sat out the Warsaw uprising because they wanted the Polish independence movement to be weakened. Churchill botched Gallipoli because he wanted to show off the power of the Admiralty. In Imperial Japan the Army and Navy were so factionalised they wouldn't collaborate with each other on any project and the Army officer corps was riddled with secret societies who took entire divisions out on adventures.

He quotes the Friends of Durruti pamphlet Towards a Fresh Revolution.

"With regard to the problem of the war, we back the idea of the army being under the absolute control of the working class. Officers with their origins in the capitalist regime do not deserve the slightest trust from us. Desertions have been numerous and most of the disasters we have encountered can be laid down to obvious betrayals by officers. As to the army, we want a revolutionary one led exclusively by workers; and should any officer be retained, it must be under the strictest supervision."But this isn't a blueprint for an army either, other than the working class being in control which in the context of the time meant the exclusion of the Republicans and Communist party. What makes an army an army and a militia a militia? Were the columns still militias? Or the Brigades?

Day's commentary doesn't enlighten

In this quote there is the usual anarchist equivocations. The defeats of the militias are the result of betrayals, but the solution is a revolutionary army. We want the workers in control but we know we will need the expertise of professional officers. This is nonetheless a considerable improvement on the naive celebration of the militias that passes for anarchist military thinking today.It says nothing about professional officers at all. There were few if any professional officers of working class origins in Spain at the time. That's largely why most of them immediately joined Franco's coalition of the right, and the ones that remained joined the right wing republicans and the communist party, the factions pushing for a moderate bourgeois government.

Its also a contradiction, how can the workers be in control if it still relies on professional officers?

If we look at the rest of the section of Fresh Revolution we find that it largely goes against Day.

We insist that the war be directed by the workers. We have grounds aplenty for this. The defeats at Toledo, Talavera, the loss of the North and Malaga point to incompetence and lack of integrity in the government circles, for the following reasons:This looks much like the usual naïve anarchist military thinking Day wants to move past.

The North of Spain could have been saved if the war materials needed for resistance to the enemy had been obtained. The means were there. The Bank of Spain had enough gold to flood Spanish soil with weaponry. Why was it not done? There was time. We must remember that the non-intervention controls did not begin to make their presence felt until the war in Spain was already some months old.

Leadership in the conduct of the war has been disastrous. Largo Caballero's record is lamentable. That the Aragon Front has not been given the arms its so needs is his fault. His reluctance to arm the Aragonese sector has prevented Aragon from assuring her own redemption from the clutches of the fascists. At the same time this could have taken the pressure off the fronts around Madrid and the North. And it was Largo Caballero who expressed the sentiment that sending arms to the Aragon Front was like handing them over to the CNT.

The question of the character of an authentically revolutionary army is important. The Friends of Durruti correctly identify the class character of the army and its command as crucial in determining its role in the revolution.….

Finally he points to the People’s Liberation Army in China as the single example of an army that carried out the revolutionary class program of the oppressed majority, namely the comprehensive redistribution of land to the poor peasantry. I have argued earlier that the Chinese Revolution was ultimately a capitalist revolution, and I would argue that the PLA carried out, at least up until 1949, a program that was consistent with the common interests of the peasantry and the aspiring new capitalist class represented by the leaders of the Communist Party. In spite of these qualifications I would argue that the Chinese experience is still an important one from the point of view of trying to develop a revolutionary libertarian military strategy.

These two final sections are instructive. Apparently the class nature of the command structure is an important factor in determining whether an army is revolutionary or not, but then we have the example of the People's Liberation Army. The PLA was founded out of the merging of several existing military forces, and the main heads in charge of the founding were Zhu De, He Long, Ye Jianying and Zhou Enlai. The Zhou's were government clerks, Ye Jianying was born to a prosperous merchant family and Zhu De was born a poor peasant but adopted by his wealthy uncle. He Long is the only one who came from a poorly peasant background.

And other major members of the PLA are Lin Biao from a merchant family. But of course this is missing the woods for the trees, the PLA is an army of the CPC, its leaders and officers are all from the ranks of the CPC, its not really a national army but a party army. It is top down and supremely hierarchical and aside from the explicit connections with the ruling party functionally no different then a conventional army. It drove out the KMT in a series of open clashes on the battlefield. And during periods of great social unrest it has shown itself the loyal defender of a stable order. During the cultural revolution it attacked and killed thousands of red guards whom were enthusiastic supporters of the CPC's leader. During Tiananmen square it launched an offensive on Beijing and killed thousands of citizens. If the PLA count as a revolutionary army than the distinction is meaningless.

And that's largely what I take away from this paper, its meaningless. Reject anarchism if you want, but there is no guide to a functional alternative here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Popular Posts

-

I've been of two minds about the Salvation Army for a number of years, the very concept of a global Evangelical army is abh...

-

Bread & Freedom by Albert Camus Speech given to the labour exchange in Saint-Etienne in May 1953. If we add up the example...

-

Sorry its a bit late (it should still be women's day for those of you to the West of me) I was celebrating Shrove Tuesday (pancake day) ...

-

Video link https://youtu.be/0sfm2DkKSOM Digitalised recording of trans rights activist Sylvia Rivera's speech at New York City...

-

My last post reminded me of the importance of the Cuban victory against South African forces in Angola in the late 80's in and around t...